Certificates SSL vs TLS: How to Deal with Them All

Why You Should Use Encryption and Certificates — Even on a Private Network

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Why Encryption Matters — Even on Private Networks

- SSL vs TLS — What’s the Difference?

- How Digital Certificates Work

- Private Root CA and Certificate Generation Process

- How the Create-and-Sign Process Works

- Use Cases for Private CAs

- Built-in Certificate Authorities in OSes and Devices

- Types of Certificates (Examples and Uses)

- Public Key vs Private Key (Asymmetric Cryptography)

- PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) — Key Elements

- Certificate Formats and OpenSSL Examples

- Tools / Applications for Generating and Signing Certificates

- Good Practices and Security Tips

- Practical TLS Configuration — Apache, SSH and Self-Signed Certs

- My Example: Signing a Wildcard for int.splunnersystem.com (Let’s Encrypt + Ansible + Cloudflare)

- What You Need for My Setup

- Notes on Automation and Security

- Final Recommendations

Introduction

Before we start using various online services, it’s worth checking whether our network enables secure communication. Using encryption via TLS certificates is not required only for large companies or public websites — it also matters in home and private networks.

Why Encryption Matters — Even on Private Networks

Encryption protects data transmitted between devices from unauthorized access. Third parties cannot read, intercept, or tamper with transmitted information.

Data transparency and integrity are key elements not only for web applications but also for other services and programs that rely on TLS certificates — for example: mail clients, messengers, cloud systems, and IoT (Internet of Things) services.

Using certificates provides not only encryption but also trust — it guarantees that we are communicating with a real, verified server rather than an impersonating device or attacker.

SSL vs TLS — What’s the Difference?

In the past, the term SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) was used to refer to the protocol for encrypting internet connections. Over time that technology was replaced by a newer and more secure protocol: TLS (Transport Layer Security).

Many people still say “SSL” out of habit, although in reality modern websites use TLS. Using the correct name signals knowledge of current standards and an understanding of modern transmission security.

TLS is technically more advanced: it offers stronger encryption, better protection against attacks, and a higher level of security compared to old SSL versions.

How Digital Certificates Work

Today, to ensure security on the Internet we use digital certificates — the current and most secure technology for proving authenticity and building trust between a user and a website.

A certificate acts like an identity document for a website. It is issued by a Certificate Authority (CA), a trusted organization that confirms that a website truly belongs to a given company or institution.

When you visit a page whose address starts with https://, your browser checks the site’s certificate. If it is valid and issued by a trusted CA, you will see a padlock icon and a notice that the connection is encrypted and secure.

Encryption means that data (e.g., passwords, logins, or card numbers) is turned into a code that is unreadable by third parties. In this way, no one can “listen in” on your communication with the server.

There are many types of certificates — from basic ones that only confirm that a connection is encrypted, to advanced certificates issued to large corporations that also verify company identity (for example EV SSL — Extended Validation).

Private Root CA and the Certificate Generation Process

Besides public Certificate Authorities that issue certificates trusted by browsers and operating systems, you can create your own private Root CA.

This is often used in closed environments: companies, test labs, corporate networks, or IoT systems. Administrators can issue and manage certificates for internal servers, devices, or users without using an external CA.

How the Create‑and‑Sign Process Works

- Generate the private key — each entity (server, application, or user) creates its own private key which is used to decrypt and sign data.

- Create a CSR (Certificate Signing Request) — based on the private key, generate a CSR containing basic information about the certificate owner (domain name, organization, location) and the public key.

- Sign the CSR by the CA — the request goes to a CA (public or private) which, after verification, signs the certificate with its root or intermediate key.

- Issue the certificate — the signed certificate is returned to the owner and can be installed on the server or device.

- Chain of Trust — the browser or system verifies that the certificate was signed by a trusted CA. For a private CA, you must add the private Root CA certificate to trusted authorities in the OS or browser in advance.

Use Cases for Private CAs

- Authorization of users or devices in closed infrastructure.

- Internal HTTPS servers (admin panels, ERP systems).

- Encrypting communication between microservices or IoT devices.

- Testing applications before production deployment.

Built-in Certificate Authorities in Operating Systems and Devices

Modern operating systems, browsers, and mobile devices integrate lists of trusted Certificate Authorities (Root CAs). This allows users to rely on preinstalled CA lists instead of manually installing certificates for popular websites.

Windows

In Windows, the list of trusted certificates is managed by the Windows Certificate Store. You can view and edit it using: certmgr.msc. Microsoft updates this list via Windows Update, so the system automatically trusts new, reputable CAs and removes those that are revoked or considered unsafe.

Linux

On Linux distributions, the trusted CA list depends on the distribution. It is commonly stored under /etc/ssl/certs/ or managed by packages like ca-certificates. Updates come through the distribution’s package manager (apt, dnf, yum). Some applications, like Firefox, use their own certificate store independent of the system store.

Mobile Devices and Others

Android and iOS phones also have built-in lists of trusted Root CAs. They also allow manual addition of certificates (e.g., corporate or school certs), often used in enterprise networks. Similar mechanisms exist in routers, IoT devices, NAS servers, and other embedded systems that rely on TLS for secure communication.

Types of Certificates (Examples and Uses)

- SSL/TLS certificate (HTTPS) — used to encrypt connections between a browser and a server.

- DV (Domain Validated) — verifies control over the domain (fast, basic).

- OV (Organization Validated) — verifies the organization plus the domain (more trusted).

- EV (Extended Validation) — most extensive verification, used where high trust is required.

- Wildcard — covers all subdomains:

*.example.com. - SAN / Multi-domain — certificate containing multiple domain names (Subject Alternative Names).

- Client certificate — used to authenticate users/devices (mutual TLS). Useful in corporate networks, APIs, and VPNs.

- Code signing certificate — used to sign applications/installers, so users/systems can verify the author and integrity (signing binaries, drivers, mobile apps).

- S/MIME (email signing & encryption) — certificates for signing and encrypting e-mail messages.

- Device / IoT certificates — issued to embedded devices to identify and encrypt device communication.

- Self-signed — signed by the entity itself (not trusted by public Root CAs). Good for testing or closed networks — the Root CA must be manually added to trusted stores.

Public Key vs Private Key (Asymmetric Cryptography)

Private key — kept secret by the owner (server or user). It is used to decrypt data, sign data, and must be strictly protected. If the private key is leaked, security is compromised.

Public key — shared openly. It is used to encrypt data to the owner or to verify digital signatures.

Common algorithms: RSA, ECDSA (ECC). ECDSA typically provides equivalent security with smaller key sizes.

In practice: the server has a private key and a certificate containing its public key; the client uses the public key in the certificate to verify identity or perform session key exchange under TLS.

PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) — Key Elements

- Root CA — the root of trust, the most important key (usually offline and heavily protected).

- Intermediate CA — used to sign end-entity certificates while keeping the root offline.

- Registration Authority (RA) — optional component that verifies identity before issuing certs.

- CRL / OCSP — revocation mechanisms to check whether a certificate has been invalidated.

- HSM (Hardware Security Module) — hardware that securely stores CA private keys.

- Certificate lifecycle — generation → issuance → renewal → revocation → archiving.

Certificate Formats and OpenSSL Examples

- PEM — Base64 ASCII with headers

-----BEGIN CERTIFICATE-----. Common on Linux. - DER — binary format, more common on Windows.

- PKCS#12 / .pfx / .p12 — container storing both certificate and private key (encrypted). Useful for Windows import / Java keystore.

- PKCS#7 / .p7b — contains certificates and chain, usually without private key.

Typical process: generate key → CSR → sign certificate.

OpenSSL Examples

- Generate private key (RSA 2048-bit):

openssl genpkey -algorithm RSA -out server.key -pkeyopt rsa_keygen_bits:2048 - Create CSR:

openssl req -new -key server.key -out server.csr -subj "/CN=example.com/O=MyCompany" - Sign CSR with your CA (issue certificate):

openssl x509 -req -in server.csr -CA ca.crt -CAkey ca.key -CAcreateserial -out server.crt -days 825 -sha256 - Export to PKCS#12 (Windows / IIS):

openssl pkcs12 -export -out server.pfx -inkey server.key -in server.crt -certfile ca.crt - Self-signed test certificate:

openssl req -x509 -new -nodes -key server.key -sha256 -days 365 -out server.crt -subj "/CN=example.local"

Note: -days 825 is an example (aligned with current best practices). Adjust according to your organization policy.

Tools / Applications for Generating and Signing Certificates

- CLI / Server CA Tools: OpenSSL, Certbot (Let’s Encrypt), CFSSL (Cloudflare), EJBCA, Microsoft AD CS, HashiCorp Vault, Smallstep (step-ca), EasyRSA

- GUI / Desktop Tools: XCA, KeyStore Explorer, Certmgr / MMC (Windows)

- Specialized: jarsigner (Java), signtool (Windows), mkcert (dev certificates)

- IoT / Embedded: mbedTLS, wolfSSL (TLS libraries for embedded devices)

Good Practices and Security Tips

- Use self-signed or private CA only in test environments; never for public services.

- Protect private keys (HSM or strong ACL + encryption).

- Use intermediate CAs — keep root offline.

- Automate certificate renewal (Certbot, ACME clients).

- Check revocation (CRL/OCSP) and configure clients properly.

- Set proper algorithms and key sizes (ECDSA or RSA 2048+/3072).

- Audit and rotate keys/certificates regularly.

- Minimize permissions on key files.

Practical TLS Configuration — Apache, SSH, and Self-Signed Certificates

Required files for TLS configuration

| File | Description | Example Name |

|---|---|---|

| Private Key | Server’s secret key for decrypting data and signing sessions | server.key |

| Server Certificate | X.509 certificate signed by CA (or self-signed) | server.crt |

| Intermediate / CA Certificate | (Optional) certificate to enable clients to verify chain | ca.crt |

Apache HTTPS Example

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerName example.com

SSLEngine on

SSLCertificateFile /etc/ssl/certs/server.crt

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/ssl/private/server.key

SSLCertificateChainFile /etc/ssl/certs/ca.crt

SSLProtocol all -SSLv2 -SSLv3 -TLSv1 -TLSv1.1

SSLCipherSuite HIGH:!aNULL:!MD5

SSLHonorCipherOrder on

DocumentRoot /var/www/html

ErrorLog ${APACHE_LOG_DIR}/error.log

CustomLog ${APACHE_LOG_DIR}/access.log combined

</VirtualHost>

sudo a2enmod ssl

sudo a2ensite default-ssl

sudo systemctl restart apache2

If using your own CA, install the root certificate on all client systems to avoid untrusted connection warnings.

SSH Server

SSH uses asymmetric cryptography but not X.509 certificates. Server keys:

- /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key (private)

- /etc/ssh/ssh_host_rsa_key.pub (public)

- User keys: ~/.ssh/id_rsa or id_ed25519 (private), ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub (public), ~/.ssh/authorized_keys (trusted keys)

You can also use OpenSSH CA to sign user/server keys:

ssh-keygen -s ca_user_key -I user1 -n user1 id_ed25519.pub

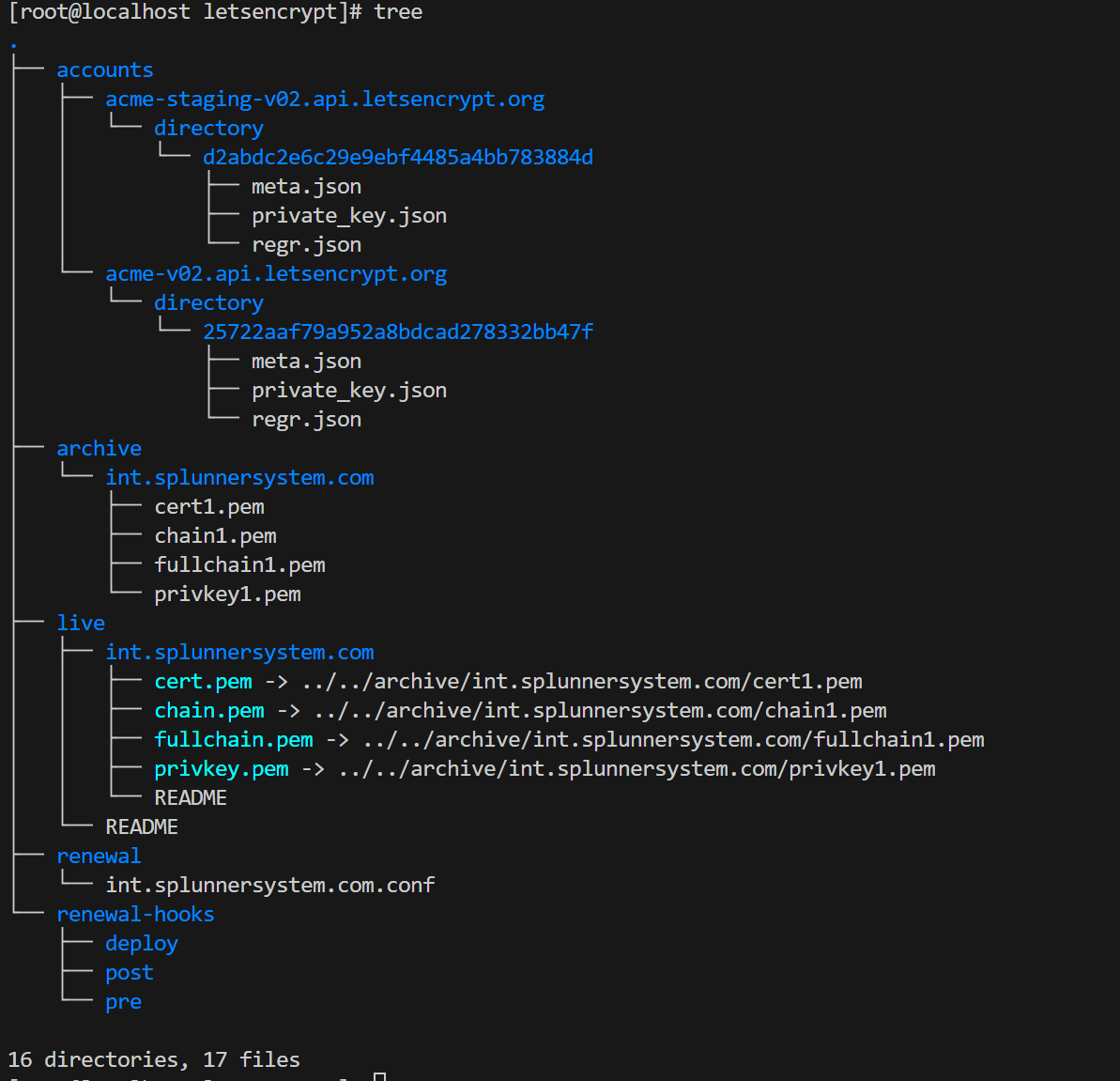

My Example: Signing a Wildcard for int.splunnersystem.com (Let’s Encrypt + Ansible + Cloudflare)

So, I have my own public domain, splunnersystem.com, one of many in my inventory, which I purchased from the registry of the Luxembourgish company EuroDNS, an ICANN-accredited registrar. Using their system, I set up the nameservers to point to Cloudflare DNS, which you can verify below or by using any DNS lookup tool. I will use this domain for my private network in my HomeLab to have secure connection.

Below you can view which subdomain will recieve wildcard certficiate which later I will use in my systems: int.splunnersystem.com . Certbot will run DNS-001 challange with Cloudfare API token.

The next step was to create an automated workflow using Ansible, defining step-by-step tasks in a role that can later be applied on the host, including custom tasks that interact with Cloudflare. This setup allows me to simply run another playbook to deploy new certificates to the appropriate configuration depending on the application, network devices, or custom services.

I do not use this for securing SSH or other sensitive connections. For those, I created a manual Root CA and generate certificates separately. I also use a different, automated approach for my Kubernetes cluster.

Below you can see a small snippet demonstrating what this setup can do and highlighting the potential of actions that I no longer need to perform manually.

To secure connections, I used a wildcard certificate with Certbot + Let’s Encrypt. My setup:

- Linux host with automation using Ansible playbooks. Where I exectute commands and store certififcates:

- Playbooks install Certbot, run certificate generation, and deploy keys across systems.

- I use a public CA (Let’s Encrypt) for web communications and my private Root CA for internal services.

What you need to the same thing on our own:

- Cloudflare account

- Your own public domain (example: splunnersystem.com)

- API token in a user file for Ansible automation

- Optional: port knocking setup for controlled access in case of connection issue.

- Linux host with ansible from where you execute commands.

- certboot installed with cloudflare plugin – This requires some Linux knowledge because is not trival due to non standard apporach. My ansible roles are handling it in simple matter of few scenarions.

Notes on Automation and Security

Using Ansible roles and tags, I create installation environments for Certbot, run generation tasks, and deploy certificates. Renewal commands are automated through Semaphore (open-source AWX alternative). Certbot with Cloudflare add txt record for the challange and after validation is removing it so your dns records are clean.

Final Recommendations

- Always store private keys securely (chmod 600).

- Do not transmit private keys unencrypted over the network.

- Use TLS 1.2 or 1.3; disable older versions.

- Enable automatic renewal for public certificates.

- Regularly test configurations (e.g., SSL Labs Test).

I really enjoyed writing this article — it covers encryption, certificates, and practical setup in a clear and detailed way. Hope you find it useful and easy to follow!

If, however, you are interested in assistance or consultation, including access to the repository of automated solutions, feel free to contact me.